Watch and Pray

Some of us, perhaps, may hear in them an echo of other occasions when Jesus uses them, or words very like them, when he encourages his followers to be on the alert for his return at the end of time, and that in itself might evoke all sorts of reactions, though this would be another talk for another day, perhaps at our next Advent day of recollection. Perhaps many of us on hearing them are anxious that we will be unable to watch and pray as we would like to do this week, and as we feel the Lord asks of us: after all, in the Garden of Olives, Peter, James and John were unequal to

the task, so how dare we assume we’ll do any better? For some of us, too, the call to watch by night may be an uncomfortable reminder of times we would rather forget, times when we have kept vigil with suffering friends or relatives, or burned the midnight oil in the face of looming deadlines; or perhaps indeed of times when we have struggled, not so much to stay awake as to fall asleep, battling insomnia, even times when we have been afraid to fall asleep, fearful of what either our dreams, or the next day will bring.

Watch and pray. There are no right or wrong answers here, no one way in which these words “should” strike us. But it strikes me, as we come to the beginning of another Holy Week, that if the Gospel is the Good News we believe it to be, there cannot be any page in our bibles which does not contain good news for us, no words of the Lord that do not speak

of the good news of God’s love and mercy. How might we hear these words of Jesus, then, not as intimidation but as invitation?

If our feelings about being asked to watch – specifically to stay awake in the night and pray, are a bit ambivalent, that’s unsurprising, and actually quite fitting, because, so too, probably, are our feelings towards night in general. And there are good reasons for this, written into our very bodies and psyches, good reason both to love and to fear the night. We may associate night-time with romance, with opportunities to kick back, to relax and celebrate when the day’s responsibilities are behind us; we associate it perhaps, with the inspiration that can come in dreams, but also with the disturbing, even the uncanny or the spooky, with nightmare and night terror. Our feelings can be heightened in all sorts of ways at night: noises can seem louder and more alarming, familiar landmarks can lose their shape and mislead us; it can be a time in which we feel set free from our workaday concerns; but it’s a time of deep vulnerability too. Medical professionals will tell us, moreover, bearing out what we perhaps know intuitively: significantly more babies are born at night than during the day;

more people die then too. There is nothing then straightforwardly comfortable about night, nothing straightforward about it at all.

Perhaps it’s not altogether surprising, therefore, and, once we’ve started to notice, it’s really striking, just how often, in the gospels, night provides the backdrop for turning points and moments of high drama. Jesus is born at night, and He rises from the dead at an hour we cannot name, but which we know to be before the dawn. And between those two great moments of birth and rebirth, between Christmas and Easter, there are so many other moments we could think about. Some of these – especially some of those we will be recalling this Holy week - emphasise night as a time for shameful deeds to be done, more easily concealed then than in the light of day. We’ll be hearing it emphasised on Friday how when Judas gets up from the supper table to betray Jesus “it was night”; His disciples flee under cover of darkness, and His trial before Caiaphas also takes place before sunrise and cockcrow. But all of them, in one way or another, I think, emphasise that the small hours

are pregnant with divine hope, even as they also reveal human frailty: think of Nicodemus, the learned Jewish leader who comes to Jesus by night, because that way he can feel secure that he will not be observed (and hears of a wondrous new birth that will enable him to see the reign of God he has longed for all his life); think of Jesus spending nights in prayer to His Father before commissioning His disciples and endowing them with His own authority to heal and set free; think of

Jesus who walks on the water, and upholds Peter as he flounderingly does the same, not merely at night, but in the fourth watch of the night, sometime in other words between 3 and 6am, in the darkest hours before the dawn, as we might say.

All of this maybe suggests that there is a particular kind of connection between the qualities we associate with night and the kind of attitude we would like to bring to our prayer. Probably all of us would like to be more open to God, more honest with him in our prayer – and there is something about the night which reveals our fragility, reminding us of how great is our need to be close to God, and which, perhaps, at least occasionally, promotes that closeness, by stripping away the

distractions that get in the way during our day-time busy-ness. And it’s surely significant, therefore – and psychologically wise – that the Church does invite us to pray during Holy Week with particular intensity at night, both on Thursday evening after the Mass of the Lord’s Supper and at the Easter Vigil.

But that still doesn’t mean that it’s easy to watch and pray, on Holy Thursday, on Holy Saturday, or ever. We might still feel daunted, even oppressed a little, by that injunction to “stay awake,” hearing it less as an invitation to the closeness to the Lord for which we long, and which we know we need, and more as an insistence that we pull ourselves together and keep going through gritted teeth in a strength we don’t possess. And here I want to suggest some very ancient resources, reaching far back beyond the events we commemorate this week, which might still console us today whenever we fear unequal to the task of watching and praying.

We know, of course, that the events of the first Holy Week occurred around the time of the Jewish festival of Passover, then as now a commemoration, and in a sense a reliving, of the events described in the book of Exodus in which the people of Israel are forth from slavery in Egypt into the promised land. Jesus longs, we are told, to eat the Passover meal, with his friends, and does so at the Last Supper, before going to the Cross, and it is for this reason that the Christian and Jewish liturgical calendars move, more or less in parallel at this time of year. It’s more or less in parallel because Passover occurs on the same days of the calendar month, rather than on the same days of the week, and this year, in fact, Passover and the Triduum map onto each other more exactly than they sometimes do.

The first evening of Passover coincides with our Holy Thursday; at the time our Jewish brothers and sisters will be asking why is this night unlike all others, as they do every year at the beginning of the Passover meal, we will be beginning the Mass which is also not quite like any other, that Mass of the Lord’s Passover supper when, as annually, we recall that “on the night he was betrayed, that is tonight” he takes bread and makes it his body, wine and makes it his blood. In some Jewish households, the Passover celebrations on Thursday evening will include the singing of an ancient song which speaks of how the Almighty “wrought many miracles wondrously in the night”, of which the liberation of the people of Israel from slavery in Egypt is the central one, the one above all commemorated on this night unlike all others, but which other mighty deeds reflect.

We have seen how, in the gospels too, God works at night, from the hour in which He reveals Himself to the shepherds in the Bethlehem stable, to the hidden moment of resurrection. But, when we look for inspiration to help us in our desire to watch and pray, when, in particular, we wonder whether we are capable of doing much by way of watching and praying, I think we might also turn especially this year when our calendars are so beautifully aligned, to the wisdom of our Jewish

brothers and sisters and reflect on the mighty deeds of the Lord which we celebrate in common with

them.

Around the time the events we commemorate this week were taking place, so either during Christ’s earthly life, or shortly after his Resurrection, a Jewish author in modern-day Iraq produced a version of the Book of Exodus, written in Aramaic, the mother tongue of Jesus and his first followers. At a certain point in his account of the liberation of the People of Israel from their slavery in Egypt, the writer interrupts his narrative with a poem, which begins by telling us “there are four nights written

in the book of memories” – and goes on to explain what they are. The night of Passover itself is the third of the four, preceded, many generations earlier, by that mysterious and terrible night, on which, as the Book of Genesis tells us, Abraham is asked by God to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac, and only spared the horror of having to do so when he finds a ram caught by its horns in the undergrowth. Before that, reaching back into the unimaginably distant past, the first of the four nights is that moment when, in the darkness at the dawn of all things, God says “Let there be light” and so the first of all days begins. But the fourth night, though it is “written in the book of memories” has not, so far as the author is concerned, happened yet. On this night, “when the world will reach its fixed time to be redeemed, the iron yokes will be broken”. This is the night when the Messiah, who is to bring about a new liberation for the people of Israel, will appear. This text is by no means an isolated curiosity. It is part of a much wider tradition which sees the Passover as taking place on the anniversary of both that troubling episode in the life of Abraham, and on the anniversary of the creation itself. The coming of the Messiah, in turn, is expected on the anniversary of the Passover. All four of these events are somehow seen here as bound together,

shedding light on each other, their meaning reverberating back and forth across the centuries, linking what has been with what is to come.

The first Christians – who were, of course, themselves Jewish – thought like this too, and there is an amazing echo of this in the liturgy we will celebrate this coming week. Next Saturday night – or, for some of us eye-wateringly early on Easter Sunday morning – we will gather by the light of the newly-lit Easter candle, and we will listen, as the Church has invited her children to do for nearly 2000 years, to a series of scripture readings. And, at any rate if we are at the Easter Vigil in a place which uses all of the readings proposed, the first three of these will be, as they have been since the earliest centuries of the Church’s history, the accounts from the Book of Genesis of the seven days of creation and the story of Abraham and Isaac, followed (wherever we are, because this one reading is compulsory) by the account from the book of Exodus of the parting of the Red Sea and the liberation of the people of Israel. We will hear, in other words, of the first three of the four nights that are written in the Book of Memories. But for us as we come to celebrate the Easter Vigil, the fourth of those four nights is not described in one particular reading, and nor is it hidden in the darkness of the future, because we believe that what our Jewish brothers and sisters look out for every Passover, often with a tender longing and an expectation that puts me at least to shame, has both already happened, and is happening before our eyes. Jesus, our Messiah, because He has passed

over from death to life, is with us in the Easter Mass as in every Mass, and more than with us, He is inviting us to take him into our very selves, giving us himself to be our food, our strength and our peace, and thereby bringing about our final liberation from all that hinders us from serving God as we long to do.

This in itself, of course, is the most fundamental reason why we can dare to hope that we might indeed have the stamina to stay awake and pray; because we need never fear we will be doing so alone, even in the darkest of our nights – and that’s a point we’ll return to, by way of looking a bit more at the third of our three nights, the night of Passover itself. But first I wanted just to say a few words about those other “nights” to which our attention is directed by both Jewish and Christian

tradition, those first two nights written in the book of memories which are also commemorated in the first readings we hear every Easter just as soon as we have lit the Easter fire and proclaimed the Resurrection. How might meditating on the story of creation, and the story of Abraham and Isaac strengthen us to keep watch, as we are asked to do this week?

One way in which our ancestors in the faith loved to think about the events of the first Holy Week was, precisely, as a second creation story. There are many beautiful echoes of this in ancient poetry and sermons, suggesting that, in His suffering on the Cross, Jesus works to recreate us, as God works to create us on the six days of creation described in the book of Genesis, with His resting in the Tomb corresponding to God’s rest on the seventh day, before He rises and sheds His light and life on and into all things at Easter.

We might think, too, of how, from the Cross, Jesus speaks seven times, echoing those seven times when, according to Genesis God speaks, and each time creation comes more fully into being. We might dare to hope that if we allow ourselves to hear Jesus speaking his wonderful words of forgiveness, entrusting and longing to us, we might become ever more who he means us to be, ever more closely conformed to his image, beautiful with his beauty, not just good, but very good. Because I think it can be profoundly helpful to reflect on the connection between creation and the Cross not simply in general terms, but in relation to myself in particular. None of us are, so to speak, finished products: we are all of us still in the process of being created, and indeed recreated. That, I think, can be a source of consolation if we are afraid that we are not able to watch and pray as fervently or as robustly as we’d like.

As we seek, rightly, to watch and pray this Holy Week, we should remember, with gratitude, that we are work in progress, that sometimes though the spirit is willing, our flesh, like that of the apostles in Gethsemane, may well be weak, and not ask the impossible of ourselves. Especially, I’d like to suggest, this is the case if we are struggling to reconcile our desire to serve Christ by accompanying Him in our prayers with our desire to serve Him in our families and neighbours, juggling multiple commitments and responsibilities. We have to be honest about our resources, and the limits of our resources: sometimes less really is more, and it can be heroically humble, sometimes, to say no. It is good to take on what we can for the Lord, but not to take on what we can’t. He understands if we slumber during our hour of watch on Holy Thursday, or if we are distracted at the Vigil by all that we have to do the next day. And we can be sure that His Spirit will continue to brood over the darkness and emptiness of our weakness, and create in us the strength we need to serve Him as He wishes to be served.

What then of the story of Abraham and Isaac? Christians have always seen in this story a prefiguration of the story at the heart of our liturgies and our prayers this week. Again, in the early centuries of the Church’s history, there are many such interpretations, with the various details of the story made to bear particular kinds of weight in a way that is simultaneously precise and almost dream-like: so, for instance, the fact that Isaac carries the wood that will be used in the burnt offering is considered to prefigure Jesus carrying His wooden cross, and Isaac himself represents, prefigures, Jesus. Then again, the ram who is substituted as sacrificial victim is also a symbol of Jesus the lamb of God. Some of the Church fathers, in fact, suggest that – as Jesus is both fully human and fully divine – the ram and Isaac stand respectively for His humanity and His divinity. It’s for this reason that in Medieval illuminated manuscripts depictions of the story are often found alongside images of the crucifixion, often in missals, because, again, it is in the Mass that we meet Jesus whose sacrifice on the Cross is symbolised by Isaac. But, though there is much food for thought here, and we could doubtless spend a lifetime meditating on it, I think that there might be another perspective on the story which, though at first sight perhaps distressing, is actually helpful, especially when we think about how we might be called to watch and pray during Holy Week, but also throughout our

lives.

Quite honestly, the story of Abraham and Isaac is a shocking one; it raises questions that are hard even to entertain, and perhaps impossible fully to answer. Why does God test Abraham in this way? The end of the story confirms, after all, that He doesn’t want him to sacrifice Isaac, so why does He pretend that He does? What does it say about Abraham that he is willing, albeit with a heavy heart to go through with this? What implications does this have for our understanding of either obedience to God, or human fatherhood? (I remember once hearing an eminent Jewish biblical scholar say that, when, as a child, he heard this story alluded to during Passover celebrations, he would find himself uncomfortably sidling away from his own father at the family dinner table, and one can see why).

These are not trivial questions, and they have haunted the imagination of theologians and artists, poets and philosophers, both Christian and Jewish throughout history. But the fact that we can’t easily answer them, I think should actually be a source of a kind of comfort, a source of strength and confidence. Sometimes our prayer, our watching in prayer, will have a similar quality of desperate uncertainty. Why does God seem to be asking this impossible thing of me, asking me to give up something I thought was his will for me, perhaps something I’ve waited for and longed for, as Abraham and Sarah longed for the blessing of children? Why am I being tested like this? What does this suffering I am undergoing, or, worse, seeing my loved one undergoing, tell me about the love of God? The story of Abraham and Isaac, and the reactions it evokes in us assures us, I think, that it is all right to wrestle in prayer with the difficult questions: not having the answers is not evidence of a failure in faith or commitment, as perhaps sometimes we too easily fear. And, of course, on Friday, as we stand at the foot of the Cross, we will hear the Lord Himself asking these questions in our voice: 'My God, My God, why...'That, too, is part of watching in prayer.

Finally, then, what of the third night written in the book of memories, the night of Passover itself? Since the earliest days of the Church, of course, Christians have meditated on the parallels between the Passover and the Passion, seeing in Jesus the new Passover lamb whose blood protects the faithful from death; seeing the events we commemorate during Holy Week as Jesus’ own passing over through the sea of death to the promised land of eternal life with the Father, bringing us with

Him as Moses led the people of Israel through the Red Sea. Once again, there is so much here for our imaginations to work on, so much here to reflect on and, for all of us, please God, the week ahead will give us the chance to do just that. But, as we prepare to enter into Holy Week once more, there’s just one last way in which reflecting on this night of all the nights written in the book of memories might help us to stay awake and keep watch with Christ, this week and beyond:

In the 12th chapter of the Book of Exodus, which forms the first reading we will hear at Mass on Thursday evening, Moses both tells the people of Israel how to prepare for the Lord’s mighty deed in rescuing them from the hand of Pharaoh, and lays down the instructions, the liturgical rubrics as we might say, for future celebrations of the Passover festival which will commemorate the events of that night and the days that follow it, for all years to come. We are told how the lamb for the

sacrifice is to be chosen, how it is to be cooked and eaten, what should accompany it at the table.

And, in the midst of this, there is something we might rather easily overlook, which we have perhaps rather often overlooked, but which I think, once we’ve noticed it, is rather amazing: Moses tells the people of Israel that, on, this night henceforth forever, they are to keep vigil, to watch and pray, in other words, as the Jewish people have indeed done at Passover ever since, sometimes at unimaginable cost and in the midst of indescribable suffering. But he gives a reason for this: the people are to keep watch on this night forever, because God has kept watch first: the night when “all the hosts of the Lord went out from the land of Egypt...was a night of watching by the Lord, to bring them out of the land of Egypt, so this same night is a night of watching kept to the Lord by all the children of Israel throughout their generations.”

Scholars of Hebrew tell us, moreover, that the verb that is translated here as watching has additional connotations: it implies care, guarding, protection. This divine watching, then is not simply a question of observing, somewhat passively, as we might watch a movie or a theatre performance; God is not merely an onlooker here, he is an active participant in mighty, liberating acts: his watching brings life from death, freedom from slavery.

So what might this mean for us as Christians, as come once again this week to commemorate, to relive, the time when Jesus passed over from death to life? Above all, I think, it might make us less anxious about our ability to keep watch, fearing that it all depends on us, because we are not, so to speak, the first or the ultimate watchers; the first and ultimate watcher is God himself. And that, perhaps might make something of a difference to how we hear those words, “watch and pray”

addressed to us this Holy Week.

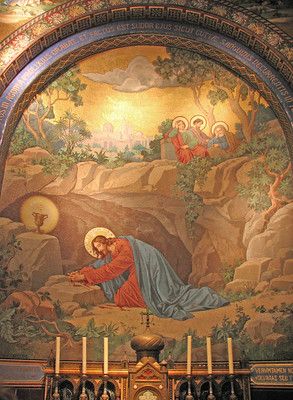

On Thursday evening, when we will recall how Jesus asked His closest friends to watch and pray with Him in Gethsemane on that night of Passover so long ago, we will be right to recognise the privilege of keeping vigil with the Lord in His suffering. We will be right especially to remember that, though Jesus has indeed passed over from death to life, the members of His body are still undergoing His suffering today, and to hold our church and our world in our prayers. But that lonely man sweating blood amid the olive trees in Gethsemane is also God Almighty. And so, on this night of Passover,

we will be right to remember that God is watching with us, watching over us to protect us, deliver us and to set us free. We will be right to bring Him our own sufferings, asking Him to shield us from danger and bring us safely through our own crucifixions to resurrection with Him.

And this, perhaps, is something for us to remember not only on Thursday, not only in Holy Week, but throughout the year, whenever we feel most daunted by the terrors of the night, whether they come upon us during the literal hours of darkness, or in those night seasons that we all experience in our lives, when, even at high noon, the sun forgets to shine.