The Seven Last Words from the Cross

By Sr. Ann Swailes

The distress of parting from those we love takes many different forms, ranging from the misery of temporary but still painful physical absence – parting may be such sweet sorrow, but it is sorrow nonetheless – to the anguish of estrangement, misunderstanding or betrayal, where the continued physical presence of the beloved feels like a wound and a mockery, to death itself, coldly shocking even when prepared for. But any of us – which I’m guessing is all of us – who have experienced any form of leave taking from those for whom we care will know, I suspect, a curious phenomenon common to all such circumstances. Seemingly inevitably, the last conversations we shared with the friends who are lost to us, or whom we fear lost to us, take on a heightened significance. We hoard up our words and theirs, and drag them out for frequent inspection, sometimes almost obsessively, investing them with a significance that we would never think of bestowing on our, or their more everyday utterances. And, frankly, at least at its most extreme, in this practice, madness sometimes lies. “And then I said…and then he said, and then I said”: we can drive ourselves to distraction this way, tearing great gashes out of our peace of mind as we examine the minutiae of our motives, and those of our friends in an attempt to reassure ourselves that all will in the end be well. And of course, we are doomed to frequent disappointment, because no human words, ultimately, can bear that kind of weight.

Today, we are here to eavesdrop on the parting of friends, as we meditate on Our Lord’s last words from the Cross. But this is different from our farewell discourses and our frantic evaluations of them, because the words we hear tonight are the words of the Word of God himself. These words, unlike our own, or those of our friends, will bear constant scrutiny, infinite examination: we could spend the entirety of our life reflecting on what he said and what he meant, and it would bring us nothing but healing and peace, nothing but an ever deeper awareness of our dignity as those for whom the Lord laid down his life, as those who are reborn in him risen from the tomb. More than that, because they are the words of the Word, the creative Word of God, if we allow them to, they will heal us, reshape us, recreate us, so that our speech becomes an echo of his. And in that lies our deepest dignity, our truest worth.

The first word: ‘Father, Forgive them.’

We are used to hearing this word, as all of the seven, year on year in our Passiontide liturgies, and so perhaps, we have become immunised against its strangeness. But it is odd, and in its oddity lies its power to turn a light on the dark places of our hearts that both sears and heals.

We do not normally think, after all, at least if we are self-respecting, well-instructed Catholics, that we need to be forgiven when we do not know what we are doing. Sin, for which we seek forgiveness in the sacrament of penance, is, precisely, deliberate wrong-doing. We explain carefully to children before their first confession that breaking mummy’s best vase by accident isn’t a sin; we reassure friends drawn to the Church but holding back because they fear the fabled oppressive power of “Catholic guilt”, that no, God is not some capricious examiner waiting to catch us out for failing to answer questions that were not on the syllabus. We are right to speak this way, very right, and right to call it to mind when we reflect on the infinite mercy of God, the mercy that went all the way to the Cross to fetch us home to our Father’s house.

And yet, as he goes to that Cross, Jesus speaks of forgiving those who do not know what they are doing. The point, I think, is an uncomfortably simple one. The Roman soldiers driving the nails into his hands and hoisting him upwards to meet his death, just one more troublemaker to be eliminated in the course of a day’s work, should have known what they were doing. Not, of course, necessarily in all its fullness: within the mysterious purposes of God, not everyone who encounters the Lord recognises his origins. There was no reason in particular why these conscripts on peace-keeping duty in Jerusalem during the flashpoint season of Passover should have the insight to see his true identity, when so many of his own people did not, and when even his closest friends were often blind to its deepest implications.

Probably, too, they were young, the lowliest of the low in the Imperial Army, frightened and brutalised raw recruits. We should not judge them too harshly. It is not our place to judge them at all.

But no one, no one at all, should be treated as Jesus was treated on that First Good Friday afternoon. And everyone, everyone without exception, should know that. So it makes more sense, I think, more chilling and disturbing sense, perhaps, to hear this last word expanded a little, into something more like “Father, they need you to forgive them precisely because they do not know what they do”. It is a merciful and life-giving precept of moral theology that ignorance reduces our culpability. But there is a kind of ignorance that is itself culpable, itself requires forgiveness.

More chilling sense, but also more consoling. This is not – let us be quite clear – because it allows us to sit in judgement over those young soldiers who acted as the instruments of state-sponsored brutality on that April afternoon nearly 2000 years ago. We have never crucified Christ, it is true, we have never crucified anyone, and we recoil in honest horror from considering in detail just what happened on that green hill far away. But that does not mean we can rest secure on the moral high ground by comparison with them.

I have suggested that the crime of those who physically put Our Lord to death lay as much in their failing to treat him as human as in their failing to recognise him as divine: many failed to see the God in Jesus; no one should have failed to see the man. But what of us? We have been given the immense gift of faith to see in the disfigured face of the despised prisoner on Calvary, the countenance of Almighty God. And we have heard from his own lips, that when we minister to our brothers and sisters in their need, we are ministering to no one less than him in whom all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell. What, then, when we fail to recognise Christ in the very place where he has promised us we will meet him, in the humanity of the poor, the lonely, the needy? Surely, of all people we are without excuse. Chilling indeed. Nothing consoling here at all.

,And yet – Father forgive them they know not what they do; Father, forgive them, just because it is their ignorance for which they need forgiveness Father, forgive us, we know not what we do. Forgive us, because we know not, even though we should. Forgive us, because only in the strength of that forgiveness can we carry on. These words are about us, too, And in that lies all our hope, all our consolation.

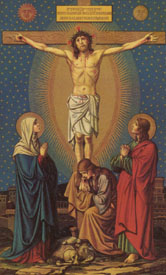

The Second Word: Woman, behold your son. Behold your mother

Mary stands at the foot of the Cross. The gospel text is bare, unsentimental, matter of fact. We are told nothing of her emotions, nothing of her body language, nothing of what she might be pondering in her heart. She simply stands with her Son, we are told, and with those few of his friends who have not deserted him. What the gospel leaves to the imagination, the great painters, poets and composers of Christian history have been quick to supply. Our Lady sings of her grief in Medieval chant, renaissance anthem and baroque aria, dressed now as a Flemish peasant, now as an Italian noblewoman, stiff or swooning according to the cultural conventions of the artist’s time and place, and she pleads for compassion on her Son in all the tongues of humanity. We might smile at the naivety of all this: we who know better, know – or at least know people, even if these people are only Wikipedia, who know- what a 1st century Galilean carpenter’s wife would really have looked and sounded like. But of course, the artistry of our tradition isn’t demonstrating historical ignorance, so much as profound spiritual wisdom, when it portrays our blessed Mother as everywoman.

The Church has always seen in this Word from the Cross more than just the tender concern of Jesus for the woman who gave him birth, in securing Mary a home in her bereavement, though of course, it is that. Rather, in naming Mary and John as Mother and Son, Our Lord is making public what has been true from the very beginning. If Mary is the mother of Christ, and we are the members, the limbs and organs of his body the Church, she is our Mother too. In the person of John, the beloved disciple, Mary welcomes all of the beloved disciples of her Son as her children, caring for them all, caring for us all, with a Mother’s love. She watches over our beginnings as she watched over the manger in Bethlehem, stands with us in our suffering as she stood on Calvary. In Christ, we are all her children.

But there is still more in this word than this. The Second Vatican Council, picking up on a theme beloved of the Fathers of the Church, tells us that Our Lady is both her Son’s first and best disciple, and an icon of the Church. If John the Beloved Disciple stands for all of us who find in Mary a tender and loving Mother, Mary herself stands for all of us too who are members of her Son’s body. We are all of us called to nurture Christ in each other, see in the sufferings of each other the sufferings of Christ and comfort them. Mary is everywoman because Mary is all of us.

The Third Word: Today you will be with me in Paradise

St Therese of Lisieux once shocked her more conventionally pious Carmelite sisters – in fact, I suspect she rather frequently did that - but on this occasion it was over her reaction to some gossip in the convent parlour. Madame X, a daily Mass goer and all round pillar of the local parish, was having a tough time: health worries piled on top of family troubles and financial anxiety – and, the nuns agreed sorrowfully, it couldn’t have happened to a nicer person. It was hard to understand how God could permit such things. Therese’s response was robust and striking: it was certainly sad about Madame X, but for her part, she said, the real question to be wrestled with was not why the godly suffer, but why the godless do. The godly after all, could be trusted to offer their sufferings in union with the Passion of Christ for the redemption of the world, and find in that companionship with the Lord at least some comfort, some resources to help them bear their own cross. The truly devastating thing was to suffer alone, and to suffer the additional, unbearable burden of meaninglessness, having nothing to do with one’s suffering other than go through with it. The sight of the unbeliever, the hostile critic of the Church in pain, thought the Little Flower, that was the real test of faith in God’s goodness in the face of human affliction. That, I think, is still quite a shocking thought, but perhaps the good nuns of the Lisieux Carmel, if they thought about it consistently, should have been still more scandalised by this Word from the Cross.

Here, after all, we are being told that it is possible, by God’s grace, for me to move instantaneously from being the kind of person about whom everyone – even myself– says that whatever filth life throws at me is no more than I deserve, to being the honoured guest at the heavenly banquet prepared before all ages. “We have received the just reward of our crimes” says the good thief: “today you will be with me in paradise” Jesus replies.

We do not know what drove the penitent thief to pray “Jesus, remember me when you come into your Kingdom.” Some have thought that he was not so much a jobbing burglar as, like Barabbas the Robber, whom Pilate released instead of Jesus at the traditional Passover amnesty, a political rebel caught up in some kind of desperate plot to overthrow the Roman occupying power, and that perhaps he perceived, somehow, at the end, an undreamed of kind of Kingship in Christ, a Kingship of gentleness and forgiveness, and longed to enlist under his colours. Others have suggested that he was motivated as much as anything by compassion for Jesus, in his own agony assuring his fellow-victim of support for his cause as the only way he could think of to bring him consolation. We simply do not know.

But in any case, what is important is the Lord’s response. Jesus does not say to the penitent thief: well done, you have passed some kind of test and consequently you will be let off what you otherwise had coming to you. He says I – I, the one who made you out of love and hold your every atom in being, will be, want to be, with you for ever. It’s not about the absence of an expected punishment: it’s about the presence of an unexpected person. And that is what salvation is, in the case of the penitent thief, and, we may hope and pray, in ours: a person, who also happens to be God, wanting so much to be with us for all eternity in paradise, that he comes to the cross to find us, and to take us home with him. We are to be with him in paradise because he wants us there. And that is a truly shocking thought.

The Fourth Word: My God, my God why have you forsaken me?

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? What can it possibly mean? What can it mean for Jesus, perfect image of the Father, very God of very God, to talk of being forsaken by his Father, abandoned by God? Great theological minds throughout the centuries have pondered, and sometimes wrangled bitterly, over what this can – and cannot betoken. And it is perhaps good that this is so, because it shows how much the truth matters. Theological debate is not, or at least it should not be, about angels on pinheads, not a matter of scoring points over those who do not think as we do for the sake of it, but about coming into ever more intimate contact with the mysteries of our faith, and, if necessary wrestling with them till they give up their life-giving secrets. But we are not here today to take part in theological debate, however well motivated. We are here to gather around the cross in unity, in praise and thanksgiving, in penitence and intercession.

And, though it is not an abdication of intellectual responsibility but an act of humility to say we cannot know fully what this terrible last word means, there is something we can know about it, something that will, if we allow it, give life to our praise and thanksgiving, our penitence and our intercession.

St Augustine loves to point out that the words of Jesus are our words: if he is the head of the Body the Church, and we that Body’s members, we speak with his voice and he with ours. When Jesus calls out in his agony, then, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me”, he is speaking, he is praying, in all our names. In the first place this is consolation for us, because it means that however distant we feel from God, however baffled and lonely we feel in the sufferings that come our way, we are doing nothing sinful in crying out to the Father who seems to have forsaken us: we are speaking, yelling, perhaps, with the voice of the sinless Word of God. But it also means something else. In the body of Christ, which embraces potentially all of humanity, we are not merely our brothers’ or our sisters’ keeper: we are our brother and our sister, because we, with our brother and sister, are Christ himself. And this gives new meaning, new motivation, to all our prayer. We can never praise enough the God who bestows this dignity upon us, never thank him enough for this unspeakable gift. Seeing our brothers and sisters as Christ himself deepens our penitence for the times we have hurt them, spurs us to pray in compassion for their needs.

As Augustine puts it:

Christ’s whole body groans in pain. Until the end of the world, when pain will pass away, this man groans and cries to God. And each one of us has part in the cry of that whole body. The body of Christ ceases not to cry out all the day, one member replacing the other whose voice is hushed. Thus there is but one man who reaches unto the end of time, and those that cry are always his members.

The Fifth Word: I thirst

I thirst. First of all, of course, the unbearable, unthinkable physical thirst, that moved his executioner to hold a sponge dripping with vinegar to the lips of Jesus, and in this act of rough compassion to a dying man, we may suppose, found himself ranged with the blessed at the Lord’s right hand: I was thirsty and you gave me to drink.

We must never forget or downplay the sheer material brutality of crucifixion, and it is right, supremely right, when we think of it, to do as St Alphonsus Liguouri suggests that we should, in his meditations on the Stations of the Cross, and “compassionate our Saviour, thus cruelly treated”. The sight of Jesus in his extreme need should move us, both to practical charity for those in whom he is crucified today, and to penitence for the manifold ways our indifference, our carelessness, our complicity with injustice, perhaps sometimes even our active unkindness, may have added to their burdens. But there is something else in this word too, something of the deepest consolation.

Once before in the Gospel, Jesus spoke of his thirst. It was to the Samaritan woman whom he meets drawing water at the public well. She goes there, in the hottest part of the day to fetch water, when she knows the fierce sun will have driven everyone else indoors, so she can avoid the prejudiced tittle-tattle of her respectable neighbours – she from the wrong side of the tracks with the dodgy marriage record: no better than she ought to be – but then, what can you expect of a Samaritan. And Jesus, tired from his journeying, sits with her by the well, and asks for a drink. He is thirsty, really thirsty, as she must be. He needs the water she is drawing as she does. Much more, as their conversation reveals, she needs the water he is offering her, the living water which cleanses sin, drives away shame, brings rebirth into abundant life. But he too thirsts for something, besides the physical water that so aptly symbolises this longing: he longs to give her that living water, to give her, that is, his love, to give her himself. And that thirst too, he suffers on Calvary. He thirsts to be thirsted for. And that thirst can only be slaked, as it was by the Samaritan woman, when we open ourselves to his love, admit our need for him, and allow him to pour his living water into our parched hearts.

Good Catholics sometimes fear, I think, perhaps particularly at this time of the year, that it is somehow wrong, or self-indulgent, to bring our own needs before the Lord when we should be concentrating exclusively on the sufferings of others, perhaps others “worse off than ourselves”. But when the sight of him in agony evokes our own need for healing, and we end up weeping for ourselves beside the Cross, we are responding to this word, helping to assuage this sacred longing. We can, of course, feed him in the hungry homeless on our streets, clothe with a kind word or an invitation the naked, shameful loneliness of that one person in our workplace, at our church, among our family circle, who never quite fits in. And, of course, we should. But when we find ourselves in the pain of rejection, or failure, or anxiety, or bereavement, whispering, or screaming, for our Lord to help us, then, too, we are seeing him thirsty and giving him to drink.

The Sixth Word: It is finished

Around this time of year, I once had a conversation with a young man sent to England from South Africa to study for the priesthood, who was full of excited anticipation at the prospect of his first springtime Easter. We, in the northern hemisphere take it for granted that the rebirth of Jesus from the tomb coincides with the burgeoning of new life in the natural world, with hedgerows and parks bursting into bloom, lengthening days and strengthening sunshine. To us, the symbolism of all this can seem almost a cliché, the stuff of greetings cards decked with impossibly fluffy chicks and dazzlingly yellow daffodils. For my seminarian friend, it was fresh, and lovely, a new thing for him echoing the definitive new thing God does for all of us in the Resurrection of his Son.

And yet, the idea of celebrating Holy Week in autumn, as my friend did at home in Port Elizabeth year on year has its own profound fittingness, too, which can help us, perhaps, truly to hear this last word: it is finished, and enter into its depths. Because, of course, when Jesus tells us “it is finished”, he is not saying it’s all over, not proclaiming himself to be yesterday’s news, not speaking of a disappointing end to a promising career. He is not speaking of an end at all, except in the sense of a goal attained, a moment of consummation reached, a precious crop gathered in and preserved for eternal life. Christ, the first fruits, as St Paul calls him, of those who have fallen asleep, is speaking of Easter as a celebration of Harvest Home.

And, in Christ, baptized into his death and resurrection, it is we who are that harvest. Human beings are so precious in the eyes of God that he came among us, precisely to gather us to himself, and bring us, rejoicing as farmers rejoice at harvest time, home to himself. That means that, even if we fear that it is all over, fear that we have never been any days’ news, tempted to think that our lives are nothing but a continual disappointment, trash to be thrown away, we could not be more wrong. We could not be more wrong either, if we ever dare to think this of anyone else, any one of the seven billion odd people alive today, or the countless hosts of human history, whom God made in his image and for whom he came among us to live, die and rise again. It is never, in that sense, finished. But, in Jesus to whom all times and seasons belong, it is accomplished.

The Seventh Word: Father, into your Hands

The 20th century English Catholic spiritual writer Caryll Houselander writes of being struck by a conversation during the London blitz with an elderly Jewish man. She asks him what coping strategies, as we might say today, he uses to deal with the fear that forms a constant backdrop to both their wartime lives. He admits to not being very religious, but says there’s one short prayer he recites regularly, a prayer that, as he tells her, “every little Jewish boy” learns to say before he goes to sleep, which he has never forgotten, and which brings him comfort. The prayer goes, he says, “into your hands I commend my spirit”.

This is the Church’s bedtime prayer, too. For those of us who say or sing the divine office regularly, these words are among the last we hear every night, during the office of compline.

And here Our Lord is addressing these words, words that, as a little Jewish boy, he will have learned at Our Lady’s knee, to his heavenly Father before he falls asleep in death. The words that bring our daily liturgy to an end bring the great liturgy of the Cross, to an end as well.

If we allow ourselves, to be shaped, in the ways we have been exploring this evening, by the last Words from the Cross, they will bring the liturgy of our own lives to an end too.

The liturgy of our lives. We think of liturgy as something we do in Church. We are looking forward already, perhaps, to the very special and beautiful liturgies in which we will participate in Church during Holy Week and over Easter. But the word liturgy does not mean, first and foremost, certainly not exclusively, something we do in Church, something bound between the pages of a Missal and governed by rubrics. The word liturgy, or the Greek words from which it comes, means, first and foremost, work, work done on behalf of the people, the community to which we belong. God, in Christ, came among us, made himself part of the human community he had created, and worked for our Salvation, thirty years in obscurity, three in public ministry, three desperate hours in which he stretched out his hands in intercession on the Cross. We, in him, members of Christ’s body through our baptism, are called to work too, by our example, even when few observe it, by our ministering to one another according to the gifts with which God has endowed us, by our prayer, and perhaps supremely sometimes by the silent prayer which is nothing but the offering of our suffering, for the salvation of the world. This is the liturgy, the work for the people God loves, for which the liturgy in Church equips us, strengthening us with the very life of Christ himself to be his body given for all humanity.

And, as we go to this work, we must frequently be forgiven when we know not what we do – and forgive others for their culpable ignorance too. We must acknowledge our own need of the healing waters of God’s love, receive with gratitude the support of Mary our Mother and our brothers and sisters the saints. We must recognise with astonished gladness that Jesus wants to be with us in paradise, and recognise too that he wants this for all of humanity, even those people who seem the most surprising. We must learn that neither we, nor anyone made in God’s image are disposable waste produce, but, rather the most precious of all harvests in his sight. We must accept that sometimes, we do not understand what is happening to us, why it has to be this way, why it has to be so painful, so lonely, so crucifying - and that it is all right not to understand. If we do all of this – and by God’s Easter grace, and only by that grace, we can – we will be able to say indeed, at the end: Father, into your hands, I commend my spirit.

Conclusion

So, seven last words. Seven words which, if we will let them, will reshape our lives after the pattern of the Word himself. Human words are inevitably limited here, chipped and cracked vessels for carrying meaning that are better than nothing, but always inadequate. We can never say all that is in our hearts when we reflect how, on the First Good Friday, God the Word fell silent.

And yet, sometimes, our stammered words speak truer than we know. A Vietnamese religious sister once gave me an unforgettable illustration of this. In pretty much every Catholic Church throughout the world, over the Crucifix four letters are written or carved, INRI, in imitation, as we know, of the title Pontius Pilate insisted on inscribing over the head of Jesus on the Cross: Iesus Nazarenus Rex Ieodaorum: Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews. The sister told me that, in at least her dialect of Vietnamese a single word, pronounced approximately – inri – and spelled as such when written in the Latin alphabet means “do this”. It is how, in Vietnamese Bibles the parable of the Good Samaritan ends: inri, or, go and do likewise At least subconsciously, then, this is what Christians in Vietnam see over every crucifix: and the history of the Church in that country, with its almost literally incredible roll-call of martyrs through the centuries, shows that they have not been slow to respond to the invitation.

But how is this possible? How can we go and do likewise? It is only possible because there is, in fact, alongside the seven last words of Our Lord that we have been contemplating today, an eighth, wordless cry from the Cross, the loud voice with which, St Matthew tells us, Jesus gave up his Spirit. Gave up his Spirit: in the first place, that is, yielded all of himself, his life of perfect obedience and goodness, into the loving embrace of his Father. But in that act of giving up, which did not concede defeat to the forces of death, but constitutes their defeat at the hands of love almighty, he gives us his Spirit, so that henceforth we may breathe with his breath, live his life, and, yes, speak with his voice the words of forgiveness, of solace, of anguish and praise that resound from the Cross throughout all of human history.

We adore you, O Christ, and we bless you, because by your holy Cross you have redeemed the world.

Amen